VICTORIA MILKO

MULTIMEDIA JOURNALIST

Made Partiana uses a net to catch aquarium fish on north coast of Bali, Indonesia, on April 10, 2021. Millions of saltwater fish are caught in Indonesia and other countries every year to fill ever more elaborate aquariums in living rooms, waiting rooms and restaurants around the world with vivid, otherworldly life. (AP Photo/Alex Lindbloom)

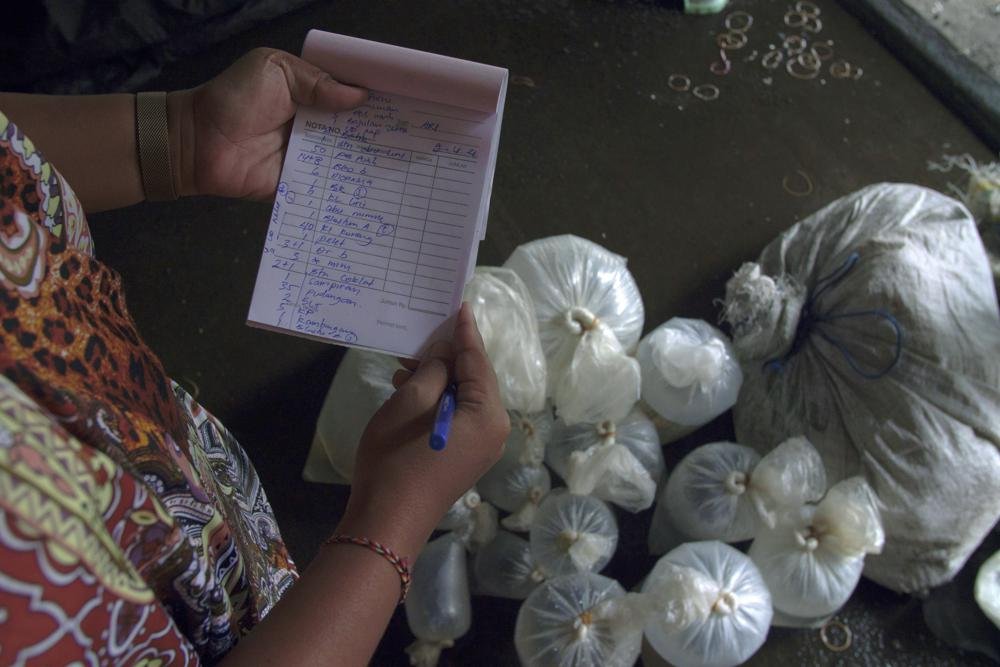

After diving into the warm sea off the coast of northern Bali, Indonesia, Made Partiana hovers above a bed of coral, holding his breath and scanning for flashes of color and movement. Hours later, exhausted, he returns to a rocky beach, towing plastic bags filled with his darting, exquisite quarry: tropical fish of all shades and shapes.

Millions of saltwater fish like these are caught in Indonesia and other countries every year to fill ever more elaborate aquariums in living rooms, waiting rooms and restaurants around the world with vivid, otherworldly life.

But the long journey from places like Bali to places like the United States is perilous for the fish and for the reefs they come from. Some are captured using squirts of cyanide to stun them. Many die along the way. And even when they are captured carefully, experts say the global demand for these fish is contributing to the degradation of delicate coral ecosystems, especially in major export countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines.

Our AP investigation traced the global supply chain from fisherman in Indonesian seaside villages, to middlemen, to export warehouses, international importers and right into homes and office buildings.

Cyanide fishing has been banned in countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines but enforcement of the law remains difficult, and experts say the practice continues.

A U.S. law known as the Lacey Act bans trafficking in fish, wildlife, or plants that were illegally taken, possessed, transported, or sold – according to the laws in the country of origin or sale. That means that any fish caught using cyanide in a country where it’s prohibited would be illegal to import or sell in the U.S.

But that helps little when it’s impossible to tell how the fish was caught. For example, no test exists to provide accurate results on whether a fish has been caught with cyanide, said Rhyne, the Roger Williams marine biology expert.

“The reality is that the Lacey Act isn’t used often because generally there’s no real record-keeping or way to enforce it,” said one expert.

Our story had fantastic imagery from freelance photographer and videographer Alex Lindbloom. While Alex worked to capture the fishing activities I just floated close by, watching as nets scooped up colorful fish.

Made Partiana, foreground, and a fellow villager bring caught fish to shore in northern Bali, Indonesia, on April 10, 2021. Partiana became part of a group of local fishermen who were taught by a local conservation organization how to use nets, care for the reef and patrol the area to guard against cyanide use. He later became a lead trainer for the organization, and has trained more than 200 fellow aquarium fishermen across Indonesia in use of less harmful techniques. (AP Photo/Alex Lindbloom)

““I saw the reef dying, turning black... You could see there were less fish.””

In the absence of rigorous national enforcement, conservation groups and local fishermen have long been working to reduce cyanide fishing in places like Les, a well-known saltwater aquarium fishing town tucked between the mountains and ocean in northern Bali.

Partiana started catching fish – using cyanide -- shortly after elementary school, when his parents could no longer afford to pay for his education. Every catch would help provide a few dollars of income for his family. But over the years Partiana began to notice the reef was changing. “I saw the reef dying, turning black,” he said. “You could see there were less fish.”

He became part of a group of local fishermen who were taught by a local conservation organization how to use nets, care for the reef and patrol the area to guard against cyanide use. He later became a lead trainer for the organization, and has trained more than 200 fellow aquarium fishermen across Indonesia in use of less harmful techniques.

For Partiana, now the father of two children, it’s not just for his benefit. “I hope that (healthier) coral reefs will make it possible for the next generation of children and grandchildren under me,” He wants them to be able to “see what coral looks like and that there can be ornamental fish in the sea.”

Myself and AP Indonesia reporter Firdia Lisnawati standing in Les village, Bali. Photo by Alex Lindbloom